Epistemic Cultures and Professional Communities in Leadership Training

In her book Epistemic Cultures, Professor Karin Knorr-Cetina explores how sciences and scientific professions create knowledge through the processes and practices in which they work. Using ethnography to study a high energy physics laboratory and a molecular biology laboratory, she was able to look at how these fields are distinct and unique entities, with different ways of thinking, being, and discovering. Even though there might be a unified approach of sorts (I.e. the Scientific Method), how that common approach gets articulated in terms of producing knowledge can be very different.

A similar understanding is introduced by John Van Maanen and Stephen Barley who spoke of occupational communities. A key point of their analysis is that there is more to work than job descriptions describe, or provided by generalized categories such as “laborer” or “programmer”. Occupations involve “social worlds” that are both under the control of organizations, as well as provide their own worlds centered on the occupation itself. Occupations can form a type of tribe that exerts its own control beyond the larger structural controls of the organization itself. Finally, there is the element of identity that is associated with any type of occupation. Our jobs can speak to who we are as people beyond the workplace, as well as who we are as people informs what kinds of jobs we are attracted to. Thus, it can be hard to dissociate our jobs from ourselves.

The implications of these points are many. They range from potential workplace conflict and cooperation, alignment and misalignment within the organization, how and who to hire, and many more. Additionally, when organizations are dominated by particular types of professions, those organizations can take on the character of that profession. Universities are influenced by academic culture and professions, but more specifically liberal arts institutions are characterized by those specific academic disciplines. Accounting firms are not surprisingly characterized accounting professional and epistemic cultures, with different types of accounting perhaps influencing different parts of the organization. The examples can go on and on.

Another classic example is the engineering firm. There is an old joke about engineers which goes, “How can you tell when an engineer is outgoing? He looks at your shoes when talking to you rather than down at his own.” While perhaps not a hilarious joke, it gets to the point that engineers are a different breed of people (and yes, despite claims to the contrary, engineers are people too). I have never worked in an engineering firm, but have known plenty of engineers. There have been times when I’ve talked to people without knowing they were engineers. Afterwards when informed about their engineering status, I’ve expressed, “Oh! That explains it.” None of this is to make fun of engineers, but rather to highlight the occupational community and epistemic culture of engineers as a unique thing. Engineers don’t just make up a profession, but a people as well.

Jennifer Chapman, leadership coach and founder of Ambition Leadership, is another person who knows quite a bit about engineers as well as other STEM professions. Part of her training in engineering culture comes from being married to an engineer. That type of participation/observational research would be enough of an exposure to the world of engineers. But beyond that is her extensive work with STEM organizations. For example, she has worked with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), National Science Foundation (NSF), the Red Cross, and others. While each of these organizations is clearly unique, what they have in common they are large structures that are dominated by certain professional cultures. As such, tailored approaches are needed to create leadership training and coaching experiences for their managers. This is where Jennifer has excelled in terms of being able to reach those audiences which can be, well, hard to reach.

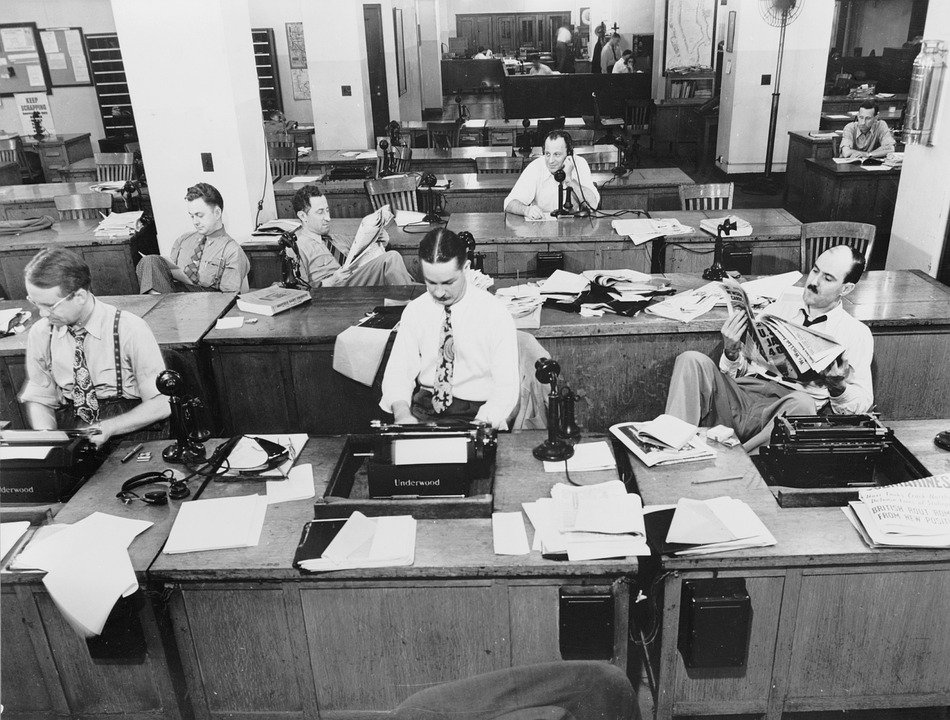

From the movie “Office Space”

Those who are working in engineering fields might get next to no training on how to work with one of the most complex machines: people. While they might want to be able to help people who work for them, they have never been shown how. Furthermore, they likely are not into the “foofy”, meaning they want to cut to the chase in terms of how to create change. While the “foof” might work well for some professional cultures, it is not as useful to others. Knowing how to design experiences for different occupational communities becomes important to make messages and content that connect with these audiences.

The field of leadership coaching has been expanding with many different types of offerings provided by just as many different approaches. At the same time, there are constants regardless of the professional culture or community. People respond better when their actions are aligned with a purpose. Also, the most effective leaders are the ones who empower their employees. Our mindset is the primary obstacle to making changes, regardless of professional background, and changing mindset is an important part of changing behavior.

But to make all of this happen, resources needed to be directed toward training and development. And not just as a general concept, but as something that is tuned and tailored to the audiences you are trying to reach. Part of employee experience is doing just that: listening to the voice of the employee and understanding the worlds in which they live. For STEM professionals, they can be data-driven and task-focused. As a result, that content and communication (rather than the foofy) needs to dominate. When you speak in the language of a culture or group, you are more likely to be understood. The important part is to understand that language and how to speak it as well.

You can listen to our conversation with Jennifer Chapman on Experience by Design below.